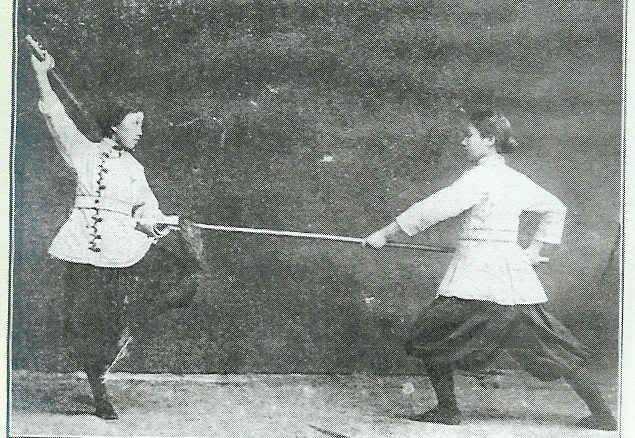

A press photo issued by the Japan Press Illustrated Service. The caption on the back reads “Instruction of Halbert and Sword.—The halbert has been instructed from old as a peculiar Japanese military art of women that trains them spiritually at the same time according to then spirit of chivalry. Photo shows girls of the Fifth girls high school of Tokyo practicing the art. (Copyrighted 231). JPI Photos.” Source: Author’s personal collection.

Introduction: Robert Jervis on Confusion and Theory

When I was a graduate student I had the very great pleasure of working as a teaching assistant (TA) for a distinguished professor of international relations named Robert Jervis. Since I had the opportunity to work with him on a number of occasions I learned a fair bit about his teaching style and even his stock stories (a good illustration goes a long way when you are trying to relate the intricacies of IR theory to real world political problems). But one of his anecdotes about the nature of theory has always struck me as particularly illuminating.

When taking Introduction to International Relations undergraduate students were required to read one or more news services daily and look for stories related to the theoretical topics that we were dealing with in the other class readings. Lectures would often begin with a short discussion of what current events revealed about the state of IR theory and vice versa. Exercises like this are nice because they allow a large number of students to enter into an academic conversation in a low stress way.

Still, Prof. Jervis is nothing if not a bit mercurial. His stories and teaching methods invariably come with a twist. During the last week of his introductory classes, just before the final exam, he always had the same conversation with his students. After discussing some item in the news and its relevance to the week’s readings, he would ask the students to sit back and reflect for a moment on what exactly they felt as they read their news blogs or watched CNN.

After all, these students had just had the privilege of spending an entire semester immersed in detailed discussions of international politics. At the end of the day all of the theories of IR are basically designed to make the chaos of international politics understandable. To separate out the signal form the noise, to reveal the essential logic of political life. And all of this material had been painstakingly introduced and discussed by someone who was both a surprisingly generous teacher and one of the great minds of the field.

Prof. Jervis would ask the class, when you sit back and read the news, how do you feel? Do you feel calm and confident? Do you understand everything that happens? Can you predict what will happen next?

This was not the sort of question that students generally wanted to answer. But eventually, after some prodding, a few people would admit that they did not feel that way at all. In fact, following the news had generally become a much less enjoyable activity. It was now a form of work. Yet beyond that it had also become irritating in ways that students often found difficult to articulate. Political leaders could be seen to do things that made no sense. Unexpected events were always rising to the fore, and the utility of IR theory in predicting anything was seen by all as pretty low.

To which Prof. Jervis would literally clap his hand in delight. He always said that when he heard this he knew that his job was done. Before the students enrolled in his class international politics tended not to be much of a puzzle. It certainly didn’t occupy much of their consciousness. Most people simply accept what happened as inevitable. Others, who are more politically inclined, might view major policy choices through the lens of domestic partisanship (that is generally the way that such events are discussed in the popular press). But everyone felt like they had a handle on what was going on.

Yet as you begin to take a much more detailed look at events in the field and the explanations for them generated by the academy, what quickly becomes apparent is that no one really has a handle on this stuff. The more you learn about the various schools of IR thought, the more puzzles begin to emerge on the nightly news. Small items that you would not have ever paid attention to before become the stuff of a graduate student’s nightmare.

Ignorance, it seems, really is bliss. Once we start to seriously examine what we know about the world, we very quickly run up against the limits of our own understanding. And that is never a pleasant process.

I never asked him about it explicitly, but in retrospect it seems that Jervis believed that it was a teacher’s job to give the students the tools that they needed to get to this uncomfortable place, to feel the puzzlement and the irritation for themselves. After that it was the student’s problem to figure out what they were going to do about it.

The discipline of political science, he would tell the students, it not meant to predict the future. Its real purpose is to make sure that new and better questions come raining down in torrents when you watch the news. To learn theory is to invest yourself in a perpetual state of struggle. To study international politics was to discover new levels of confusion. He would then remind the students exactly how much they had paid in tuition for the semester, and ask them whether they thought they had gotten their money’s worth? As I said, he was nothing if not mercurial.

An Afternoon with T. J. Hinrichs

Recently I found myself pondering the lessons of that final discussion with Prof. Jervis. What can one really accomplish in a single undergraduate class? On the one hand these students had learned just enough IR theory to be truly dangerous. Yet looking back I think that we can all remember that there is no more exciting time to be a student.

This same sense of excitement caught up with me earlier this week. Prof. T. J. Hinrichs teaches in the history department of Cornell University. Her research focuses on the development of ancient Chinese medical practices. She is also a dedicated martial artist (Aikido) and she had more than a passing interest in martial arts studies.

In fact, she periodically teaches a class titled the History of the East Asian Martial Arts (HIST 2960/ASIAN 2290). The class is geared towards undergraduates and meets twice a week for a full semester. Anyone interested in checking out her fascinating reading list (and you should be) can see what she is assigning here.

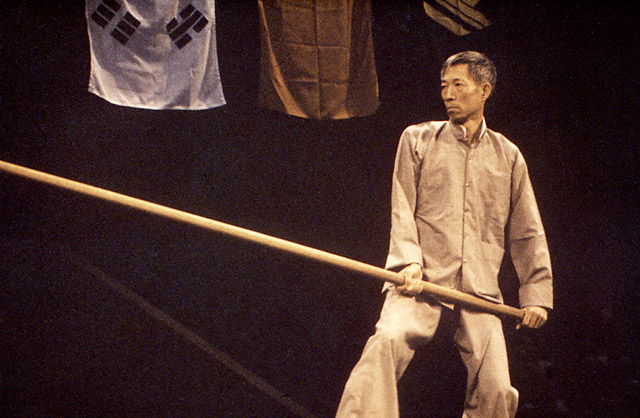

Earlier in the semester Prof. Hinrichs let me know that she had assigned her students a chapter from my book and she invited me to drop by and discuss some Wing Chun history with respect to Chinese approaches to the question of “lineage transmission” within the martial arts. But this introduction to the subject was only meant to take up part of the class time. The rest of it was dedicated to a discussion of the readings and the idea of lineage in a comparative (Chinese vs. Japanese, ancient vs. modern) context. Also in attendance was Maofu Gong, a visiting Prof. of Wushu from Chengdu Sport University who is currently working with the Cornell East Asia Program.

I cannot really speak to the quality of my own remarks, but what I saw happening in that classroom was very exciting. Listening to the students review their readings (which in addition to my own chapter included Hurst’s pioneering Armed Martial Arts of Japan as well as Jeff Takacs’ article “A Case of Contagious Legitimacy: Kinship, Ritual and Manipulation in Chinese Martial Arts Societies“) was enough to give me a serious case of academic jealousy.

Do these students actually appreciate the value of what is going on in their class? One suspects that the answer is probably no. At least not yet. How could they?

It took me years to find the authors and resources to assemble a reading list comparable to the one that these students had just been handed on the first day of class. Yet if you have never been forced to go through the exercise yourself it might be difficult to realize the intrinsic value that lies in something as seemingly simple as a syllabus.

Theoretical knowledge, in practically any subject, is interesting in that it seems to have escaped the rules of economic gravity that govern most of the other goods that people produce. Generally the law of diminishing marginal returns guarantees that the more you have of something, the less benefit each additional unit brings. Yet in a field like martial arts studies the value and interest of the next level of understanding is based rather directly on how much you already know. The more material that you have already been exposed too, the greater the insights that you can gain from the next book or article. The undergraduate students were still working hard at building their basic foundations of historical understanding, but for the more experienced scholars in the room, each discussion topic was ripe with possibilities.

Still, as I look back on the class I realize that the most interesting thing was not the quality of the reading list or even the discussion itself. Rather it was the environment that it was all happening in. When I began to think about these issues my academic career and my martial arts interest were two distinct things. They happened in different physical, and even mental, spaces. Finding a way to bring them together was a challenge.

The experiences of the students in this class, and the expectations that they are forming about the place of the martial arts in the academy, are radically different. It is not only that they now have a chance to discuss the evolution of Budo or Wushu in academically rigorous ways. But this is happening in an environment in which it is simply expected that anything you discuss will also be connected to the broader questions of history, sociology, critical theory and even economics (interestingly a lot of the students in the class were actually economics majors).

The speed and facility with which the class moved between a discussion of the evolution of Choy Li Fut in Guangdong and the alienation of labor during periods of rapid economic development was interesting. Debating the implications of the development of martial arts folklore traditions for how we should understand the evolution of proto-nationalist sentiments in China was fascinating.

These were approaches, concepts and ideas that, working in isolation, I spent years trying to wrap my mind around. And yet for the next generation of students they have become the starting point for any sensible discussion of martial arts studies. Nor is this class an isolated occurrence. There are an increasing number of universities around North America that offer similar classes, and even more professors who are bringing this material into other sorts of courses as new lecture material or special modules.

My afternoon with Prof. Gong and Prof. Hinrichs left me with one very solid conviction. Martial arts studies as a discipline is about to explode. We have seen gratifying growth in the realm of publication as more journals and university presses accept our projects. The uptick in conferences and networking opportunities has been gratifying. And it is increasingly possible for scholars to discuss their research without the sorts of extended apologies that tended to accompany work that was being published even a decade ago.

Yet most of these gains were made in an era when only a few stalwart pioneers were actually teaching this material to undergrads. The current generation of students of students is poised to do fascinating things. They will be just as skilled in the arts and sciences as their predecessors. But unlike most martial arts studies scholars from my generation, they will have been integrating a broad range of works on this subject into their thinking throughout their time as undergraduates.

They will have been in the very unique position to consider, critique and study this material at the same time that they are being introduced to classic concepts and cutting edge research techniques in their other courses. They will be entering graduate programs with puzzles and research questions already in mind. Best of all, they will be emerging as young scholars into an environment in which conferences, monographs and journals dedicated to martial arts studies are increasingly common and accessible.

In the past few years martial arts studies has made immense progress. Yet I predict that it will pale in comparison to both the volume and sophistication of the work that we will be seeing in the next few years. This is going to be a very exciting time. And yet much of the critical work being done to lay the foundations for this eruption is happening quietly, almost entirely out of sight, in classrooms around the country. Of course this is how academic revolutions typically begin. Consider yourself warned.

Does this mean that we are on the verge of solving the critical puzzles of martial arts studies? Prof. Jervis would smirk at the thought. Rapid progress has a way of bringing fresh confusion in its wake. Ultimately that is a good thing. Perhaps the great contribution of this new generation of better trained students will be to see the key issues in need of discussion more clearly than their predecessors.

oOo

Are you interested in reading more about Martial Arts Studies in the classroom? If so take a look at:

Will Universities Save the Traditional Asian Martial Arts?

Martial Arts: So What? By Adam D. Frank

Martial Arts Studies: Answering the “So what?” question

![Representatives of Chinese Sanda fighters participate Wednesday's news conference. [Photo provided for chinadaiy.com.cn]](http://chinesemartialstudies.files.wordpress.com/2015/12/sanda-news-conference.jpg?w=750)